Today we examine ethology, aka the process of interviewing an animal in its own language. We start at the turn of the century. Freud and William James have established psychology as an introspective field of study, more philosophy than science. This in between standing occasioned a revolution within the field, resulting in a transformation that placed behaviorism on top. The behaviorists offered a quantitative method that made psychology seem like more of a science than a field for rumination. Thus it became an experimental, data driven field that distrusted any behavior that could not be seen or measured.

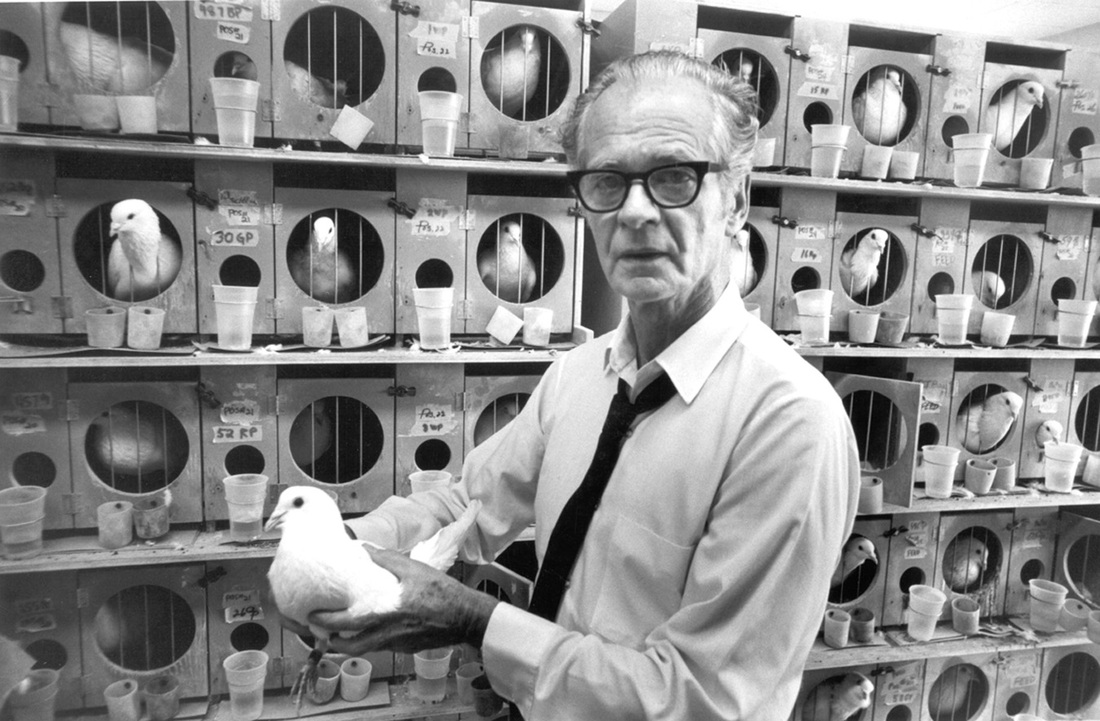

Thus there was no interest in what was going on inside - all that mattered were what happened in the environment right before the behavior and what behavior was produced (stimulus-response). Everything else was dismissed as speculation. The field reached its peak influence with B.F. Skinner (whose work was really just a repackaging of concepts introduced earlier by Thorndike).

Key features:

1.Radical environmentalism - we are blank slates whose behavior is determined by the environment.

2. Reinforcement theory - with control of positive and negative reinforcement along with control of punishment you can produce whatever behavior you want in an organism. (Quick note: positive reinforcement is a reward for a behavior; negative reinforcement is a reward via the removal of something bad - think pain medication; positive punishment is actual punishment - think pain; negative punishment is removal of something good - think of Mom taking away your iPhone.)

3. Notion of universality - it works the same for everyone.

Thus there was no interest in what was going on inside - all that mattered were what happened in the environment right before the behavior and what behavior was produced (stimulus-response). Everything else was dismissed as speculation. The field reached its peak influence with B.F. Skinner (whose work was really just a repackaging of concepts introduced earlier by Thorndike).

Key features:

1.Radical environmentalism - we are blank slates whose behavior is determined by the environment.

2. Reinforcement theory - with control of positive and negative reinforcement along with control of punishment you can produce whatever behavior you want in an organism. (Quick note: positive reinforcement is a reward for a behavior; negative reinforcement is a reward via the removal of something bad - think pain medication; positive punishment is actual punishment - think pain; negative punishment is removal of something good - think of Mom taking away your iPhone.)

3. Notion of universality - it works the same for everyone.

Skinner penned Walden Two, an ode to the use of operant conditioning to build a better society. A cheeky title, too, since it's hard to imagine a historical figure who would dig the concepts of behaviorism less than Henry David Thoreau.

As simplistic as the theories sound, they still hold considerable sway in the field today. One need only consider the medical model of treatment to see that the notion of stimulus-response hasn't died down all that much.

The ethologists stand in contrast to the behaviorists because they believe in interviewing animals in their own language and because they collected mountains of data showing variety in behaviors rather than simplistic similarity.

(As a side note I see a commentator on YouTube has suggested that Sapolsky misrepresents Skinner's ideas. I'm no fan of Skinner and won't be coming to his defense. That said, some elements of behavioral theory have validity and anyone who's interested in this area may find it worth exploring. In my opinion what they got right were the obvious points that anyone could see - such as you're likely to engage in rewarding behaviors more than unrewarding ones - but they fall off the tracks completely at the more complex and subtle levels, those involving motivation, self-destructive behaviors and psychological hang-ups - you know, the raison d'etre of the field of psychology...)

The founding fathers of ethology are Nikolas Tinbergen, Konrad Lorenz and Karl von Frisch.

As simplistic as the theories sound, they still hold considerable sway in the field today. One need only consider the medical model of treatment to see that the notion of stimulus-response hasn't died down all that much.

The ethologists stand in contrast to the behaviorists because they believe in interviewing animals in their own language and because they collected mountains of data showing variety in behaviors rather than simplistic similarity.

(As a side note I see a commentator on YouTube has suggested that Sapolsky misrepresents Skinner's ideas. I'm no fan of Skinner and won't be coming to his defense. That said, some elements of behavioral theory have validity and anyone who's interested in this area may find it worth exploring. In my opinion what they got right were the obvious points that anyone could see - such as you're likely to engage in rewarding behaviors more than unrewarding ones - but they fall off the tracks completely at the more complex and subtle levels, those involving motivation, self-destructive behaviors and psychological hang-ups - you know, the raison d'etre of the field of psychology...)

The founding fathers of ethology are Nikolas Tinbergen, Konrad Lorenz and Karl von Frisch.

He notes studies on enriched environments done in the 1960's that demonstrated that a rat's cortex was thickened by being placed in an enriched environment. But another study showed that when rats from the wild were captured and their cortical thickness was checked, their cortex was thicker than the rats from the enriched environment. In other words, you've got to check animals out in their real environment - no lab setup will ever give you the same results.

Next he introduces fixed action patterns. These are behaviors that are linked in with instinct/genes in subtle ways. They are triggered by an environmental release stimulus. What's the internal mechanism? And what's the value?

Fixed action patterns - set of movements/actions that are wired, but which an animal has to learn how to do better (when and how). For example even without a role model, a squirrel would still know how to crack a nut. With practice they get much better.

The visual cliff response is mentioned, with all kinds of species freaking out, except a sloth which is wired to being used to such visions.

Vervet monkeys have fixed action patterns for alarm calls (scary thing below, scary thing above) but they have to learn to use them correctly. An infant may shriek out an alarm call but no one's moving until an adult confirms. Sometimes they have the basic idea right (Yikes, predator) but they panic and call out the wrong instructions. With experience the fixed action pattern grows into a reliable behavior. Thus they move when the adult calls out the play.

Infant smiling is a classic example of a fixed action pattern in humans. Fetuses smile. Blind babies smile. Nursing is also a fixed action pattern.

Von Frisch performed interesting studies on bees, deciphering that they do their little figure 8 dance in the hive to establish the location and quality of food. One of his experiments included creating a food source in the middle of a lake. The bee then heads back and tells everyone about it. They laugh, since it's in the middle of the lake. In another one he rotated the hive so the directions were wrong. The studies were suggested by Jack Handey.

The Harlow monkey studies featured two wire monkeys, one with milk and the other with soft fabric. Baby monkeys were separated from their mothers and given a choice between the two. While the behavioral model suggests that they'd go for the milk (nourishment being reinforcing), the baby monkeys actually prefer the psychological comfort of the soft wire monkey. A human parallel was seen with premature/at risk babies that were kept in special care at hospitals. Reasoning that nourishment and warmth were the keys to care, hospital staff curbed parental visits to 30 minutes a week and, with the introduction of incubators, began limiting all kinds of touch. Sadly this resulted in shorter lifespans and worse outcomes wherever incubators were found. Fortunately the radical idea of actually touching the babies was reintroduced and outcomes improved.

Studies demonstrate that female rhesus monkeys have to learn how to be effective mothers - the behaviors aren't instinctual. Later offspring have a better chance of surviving. Having an older "sister" also leads to better outcomes. Modeling.

Meerkats learn how to kill scorpions step by step. Mom brings a dead scorpion first so the child learns how to eat it without getting hurt. Next she brings a live scorpion without the stinger (which she's bitten off). Finally, once those lessons have been mastered she presents a regular scorpion.

Apes make tools. The more experience watching and learning by experience, the better they are. Female chimps learn more quickly than males because the females actually pay attention to Mom.

One trial learning. Example of birds imprinting on mom. First big thing is the thing to follow. Some sort of neurological wiring to guide you.

Sauce Bearnaise syndrome - get nauseous and food correlated in time with the experience will trigger the same response the next time you smell it. Prepared learning.

Are humans innately scared of spiders and snakes? No, but we have very strong prepared learning for it. Cultural factors can overcome this but the amygdala is ready to be frightened - it takes a much smaller stimulus to get us going in that direction.

Next a relatively sad section - do animals have self awareness? Studies focusing on whether animals examine themselves in the mirror or not. Bit of human arrogance here. Also an example of the limited boundaries of science - measuring only what it's designed to measure and ruling out what it doesn't have the capacity to measure as unreal. Good juxtaposition by Professor Sapolsky since the section before was on echolocation. What science doesn't know how to measure is unreal until science catches up and then science gets a little arrogant.

This is the epistemological function of knowledge - we think the thinkable thoughts but not the unthinkable ones.

Marmosets don't stare into other marmosets' eyes. Thus they failed the forehead spot test until it was placed on their throat instead.

Theory of mind - not everyone sees the world the way you do.

Next he introduces fixed action patterns. These are behaviors that are linked in with instinct/genes in subtle ways. They are triggered by an environmental release stimulus. What's the internal mechanism? And what's the value?

Fixed action patterns - set of movements/actions that are wired, but which an animal has to learn how to do better (when and how). For example even without a role model, a squirrel would still know how to crack a nut. With practice they get much better.

The visual cliff response is mentioned, with all kinds of species freaking out, except a sloth which is wired to being used to such visions.

Vervet monkeys have fixed action patterns for alarm calls (scary thing below, scary thing above) but they have to learn to use them correctly. An infant may shriek out an alarm call but no one's moving until an adult confirms. Sometimes they have the basic idea right (Yikes, predator) but they panic and call out the wrong instructions. With experience the fixed action pattern grows into a reliable behavior. Thus they move when the adult calls out the play.

Infant smiling is a classic example of a fixed action pattern in humans. Fetuses smile. Blind babies smile. Nursing is also a fixed action pattern.

Von Frisch performed interesting studies on bees, deciphering that they do their little figure 8 dance in the hive to establish the location and quality of food. One of his experiments included creating a food source in the middle of a lake. The bee then heads back and tells everyone about it. They laugh, since it's in the middle of the lake. In another one he rotated the hive so the directions were wrong. The studies were suggested by Jack Handey.

The Harlow monkey studies featured two wire monkeys, one with milk and the other with soft fabric. Baby monkeys were separated from their mothers and given a choice between the two. While the behavioral model suggests that they'd go for the milk (nourishment being reinforcing), the baby monkeys actually prefer the psychological comfort of the soft wire monkey. A human parallel was seen with premature/at risk babies that were kept in special care at hospitals. Reasoning that nourishment and warmth were the keys to care, hospital staff curbed parental visits to 30 minutes a week and, with the introduction of incubators, began limiting all kinds of touch. Sadly this resulted in shorter lifespans and worse outcomes wherever incubators were found. Fortunately the radical idea of actually touching the babies was reintroduced and outcomes improved.

Studies demonstrate that female rhesus monkeys have to learn how to be effective mothers - the behaviors aren't instinctual. Later offspring have a better chance of surviving. Having an older "sister" also leads to better outcomes. Modeling.

Meerkats learn how to kill scorpions step by step. Mom brings a dead scorpion first so the child learns how to eat it without getting hurt. Next she brings a live scorpion without the stinger (which she's bitten off). Finally, once those lessons have been mastered she presents a regular scorpion.

Apes make tools. The more experience watching and learning by experience, the better they are. Female chimps learn more quickly than males because the females actually pay attention to Mom.

One trial learning. Example of birds imprinting on mom. First big thing is the thing to follow. Some sort of neurological wiring to guide you.

Sauce Bearnaise syndrome - get nauseous and food correlated in time with the experience will trigger the same response the next time you smell it. Prepared learning.

Are humans innately scared of spiders and snakes? No, but we have very strong prepared learning for it. Cultural factors can overcome this but the amygdala is ready to be frightened - it takes a much smaller stimulus to get us going in that direction.

Next a relatively sad section - do animals have self awareness? Studies focusing on whether animals examine themselves in the mirror or not. Bit of human arrogance here. Also an example of the limited boundaries of science - measuring only what it's designed to measure and ruling out what it doesn't have the capacity to measure as unreal. Good juxtaposition by Professor Sapolsky since the section before was on echolocation. What science doesn't know how to measure is unreal until science catches up and then science gets a little arrogant.

This is the epistemological function of knowledge - we think the thinkable thoughts but not the unthinkable ones.

Marmosets don't stare into other marmosets' eyes. Thus they failed the forehead spot test until it was placed on their throat instead.

Theory of mind - not everyone sees the world the way you do.